Many a compliance practitioner would tell you the Enron scandal and subsequent passing of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 mark the origin of the profession as we know it.

Haluk Ferden Gursel wouldn’t. And he wouldn’t call compliance a profession, either.

Gursel, honored for Lifetime Achievement in Compliance at the 2023 Excellence in Compliance Awards, speaks from his background as a longtime expert on combating fraud. It was in the 1970s, while he was working as an auditor, that he saw compliance take form as a discipline in the aftermath of the Lockheed bribery scandals that played part in inspiring the passage of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act in 1977.

Discipline. Not profession.

“It has not matured to a profession yet because we don’t have common rules, balances, and standards,” said Gursel of compliance. “… The standards are something that should be wide.”

Gursel does not say this as a critic of compliance; rather, he is a proponent. His career, most notably his time with the United Nations, has put him at the forefront of many initiatives germane to compliance today. First drafts of UN guidance regarding fraud prevention, ensuring accountability, and oversight of third-party suppliers—each included significant input as a resource person from Gursel that can still be felt in their latest iterations.

“I like the firsts,” said Gursel with a smirk.

Gursel has shared his knowledge and experience in at least 80 countries, by his daughter’s count. He has been awarded and recognized for his achievements in anti-fraud, leadership, and finance and accounting.

Even a recent back injury—his “biggest sorrow”—hasn’t stopped Gursel from his work. He took the call for this profile from Istanbul, a pitstop on his way to the United Arab Emirates and his next assignment.

Career overview

In his early years as an auditor, Gursel likened his appearance to that of famed TV detective Columbo: smoking pipe, casual look, overcoat. Unlike Columbo, however, he was writing his own scenario not knowing the end beforehand, he joked.

His colleagues preferred to refer to him with another pop culture reference.

In Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the supercomputer HAL 9000 is a sophisticated artificial intelligence onboard the Discovery One spaceship. Though the technology—spoiler alert for a 55-year-old movie—ultimately becomes the film’s primary antagonist, Gursel’s peers calling him “Hal” was complimentary in nature.

“They said that because I was solving problems quickly,” he said.

Still, some might have seen Gursel as an antagonist. Such was the perception of auditors during that era.

“We were respected—but feared—at the time,” Gursel said. “… There were no other considerable controls than the audit. That was not welcomed.”

Soon the function branched into risk assessment, then into detecting and examining fraud. Gursel continued along this career path, eventually settling in as an adjunct professor at Webster University in Switzerland, where he taught anti-fraud courses from 1982-2013.

More Excellence in Compliance Awards

- CCO of the Year: Great connector Bill Burtis celebrated by colleagues

- Compliance Program: Amex GBT navigates tricky 2022

- Compliance Innovator: Data-driven disruptor Bianca Forde

- Compliance Mentor: Q&A with Rachel Simon

- Rising Star: Q&A with Anastasia Savvateeva

“When you learn too much, you need a sounding board,” he said of his career transition. “And that can’t be your wife. Don’t torture anyone.”

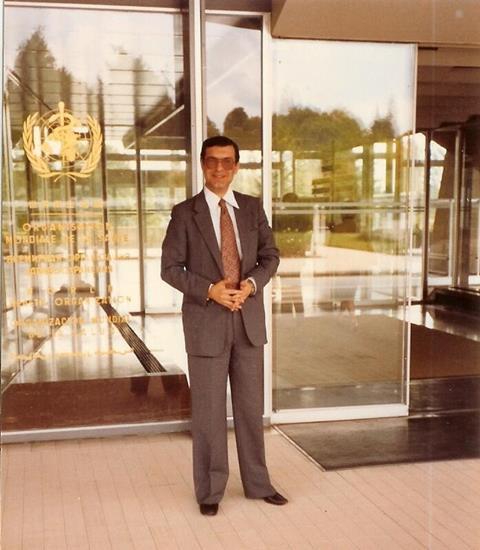

Gursel’s courses were unique in that he introduced what he’d learned from his time attending the University of Maryland in the United States. “I’m more American-oriented in my knowledge, whereas European investigations are different,” he said. He taught Association of Certified Fraud Examiners courses—a first in continental Europe—and made a name for himself that led to instructing engagements at German shipping giant DHL, the World Health Organization (WHO), UNAIDS, the United Nations Development Programme, and more.

“I learn and I confess that I learn because I wasn’t born like this,” he said of his approach. “I learned everything either from guides, people, reading, or talking. I never stole the ideas—that you can be sure of. Either I created or I mentioned.”

Impact at WHO, United Nations

Gursel served in the internal oversight department with the WHO from 1980-2006, where his work took him to North Korea, Africa, the Americas, and other regions to help sniff out fraud. In 2006, he contributed to the drafting of the organization’s quality assurance scheme.

“He was probably the best ‘rules-based’ financial auditor that I ever met,” said Georg Axmann, who worked for the organization in the same office as Gursel over a three-year period. “In addition, his phenomenal memory and ability to analyze even the most complex financial transactions … far exceeded the ability of most auditors in the UN system, even including those at a higher formal rank.”

Gursel became a diplomat for the United Nations in 1991. He still serves the intergovernmental organization as a consultant today.

One of his standout achievements at the United Nations came in 2005. Kofi Annan, then serving as the UN’s secretary-general, said he didn’t want to leave without a fraud prevention policy in place. The organization sought out Gursel as a resource person to help prepare its first draft.

The professor approached the assignment with a novel concept in mind: accountability. Fraud was a cold word, he said, and accountability seemed its natural inverse.

“If there’s accountability, there’s no fraud,” he said, likening the relationship between the two to the duality depicted in the image of the two-faced Roman mythological figure Janus.

Gursel’s policy broached another fairly new concept at the time in ethics. The World Bank in 2005 had agreed to an ethics function, which stated ethics had to be separate from investigations.

“Now I start becoming a compliance person,” Gursel remarked, “but it was the correct path.”

He served as chief compliance enhancement officer at UNAIDS, where he “played an instrumental role in building a culture of risk management, compliance, and accountability in the organization,” said Joel Rehnstrom, the program’s director of financial management and accountability at the time. Rehnstrom described Gursel as “a thinker” who brought professionalism, commitment, and passion toward the job.

“In my life, we had many less-successful programs and projects; this stands out as something where we have had a sustained impact,” Rehnstrom said. “Things haven’t fizzled out; it’s provided the basis for work going forward.”

Friend of the fraudsters

One story Gursel shared came from his time as a professor at Webster, when he was informed by the dean the police had called for him. A student of his was suspected of hacking bank accounts and told the authorities he had learned about fraud from Gursel’s class.

“If you don’t tell them about how to fraud, how can they detect where is the fraud?” Gursel told the officer. The school would later be instructed students taking Gursel’s courses should be required to sign a document promising the knowledge gained would be used in the right way; Gursel said he doesn’t recall if he ever received such an agreement from a student.

To Gursel, there is no learning fraud prevention without understanding those who carry out the misconduct. He counts convicted fraudsters among his close friends.

“We have to talk to them and get the stories,” he said.

Gursel’s story remains unfinished. His current work is exploring the bounty of fraud and how fraud not discovered adds to the fortune of the next generation of fraudsters. He continues to be an eager-to-learn student on the subject, in search of his next “first” that can inspire the work of others behind him.

“If they are imitating it, that means they like it,” he said.

No comments yet