For major financial institutions, multiple risk factors affect whether to keep or exit a high-risk relationship with an ultrawealthy client.

“Reputational risk, risk of class-action lawsuits, and regulatory risk are the three big ones,” said Karim Rajwani, an independent anti-financial crime consultant.

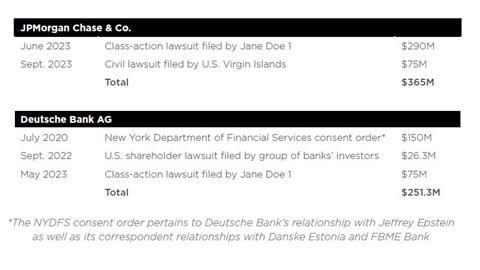

The Jeffrey Epstein-related lawsuits filed and regulatory penalties levied against JPMorgan Chase and Deutsche Bank bear out the significance of these categorical risks. The price tag of doing business with Epstein was in the hundreds of million for both institutions—not including the cost of remedial measures, such as internal investigations and monitorships, and the financial consequences of reputational damage.

Neither Deutsche Bank nor JPMorgan responded to requests for comment on these settlements.

It is clear both institutions retained the Epstein relationship for too long. In class-action lawsuits, both banks were accused of acting in reckless disregard of the fact the Epstein sex-trafficking venture used means of force to coerce young girls and women to engage in commercial sex acts.

Yet, there is a case to be made for why exiting a high-risk relationship too soon can become an inverse form of recklessness.

“Regulators have challenged institutions that exit relationships on a mass scale. It’s called de-risking, and regulators have a problem with that because it does impact the underbanked and unbanked,” Rajwani noted.

Exiting too soon is especially problematic when the risk of money laundering is heightened, he said.

“If you file numerous suspicious activity reports, what you don’t want to be doing is participating in potential money laundering activities. At the same time, you do want to be careful that you don’t exit too early because the individual will just take the money and go somewhere else. You don’t want to let them walk away with fraudulent funds,” Rajwani said.

If an institution has reasonable grounds to suspect a client of money laundering, it should not feign plausible deniability—as JPMorgan and Deutsche Bank allegedly did—but rather, contact law enforcement.

“If it’s a major money laundering case, often you may want to talk to law enforcement and say, ‘Hey, we are planning to exit this relationship. Do you have any concerns? Do you want us to keep it open?’ Typically, institutions go on something like a comfort letter to say, ‘Hey, we can keep it open, but we need something to protect ourselves,’” said Rajwani.

The issue with SARs

A defense of financial institutions is that they have a limited view into the likelihood of criminal activity beyond the filing of suspicious activity reports (SARs).

“There’s a process of identifying potential suspicious transactions; investigating them to assess the suspicious nature; and then, if determined to be potentially suspicious activity, filing a SAR with the U.S. Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN),” Maria Vullo, former superintendent of the New York State Department of Financial Services (NYDFS), said.

There are various means of identifying potential unusual activity, which Rajwani bucketed as:

- The institution’s transaction monitoring system;

- Referrals by internal staff members; and

- Referrals by external sources, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation or other financial institutions (FIs).

An internal investigations team then assesses whether the institution has reasonable grounds to suspect money laundering or the proceeds of crime on the basis of these sources. Once the “reasonable grounds” standard is achieved, a SAR is filed.

The Bank Secrecy Act/Anti-Money Laundering (BSA/AML) Examination Manual published by the U.S. Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council stresses the importance of an effective SAR program from a national security perspective. SARs are “critical to the United States’ ability to combat terrorism, terrorist financing, money laundering, and other financial crimes,” the manual states.

SARs filings are highly confidential. Banks are strictly prohibited from disclosing the existence of a SAR to a customer.

“To tip a client that a SAR has been filed on [him or her] is a tipping offense. Under no circumstances must the client know. So, the question becomes: Who in the organization should know? Typically, the fewer, the better,” said Rajwani.

To obfuscate matters further from the bank’s perspective, the transmission of information in a SAR is typically one-sided.

“From the government perspective, FinCEN and a number of law enforcement agencies throughout the country have access to the SAR database. … For the government, it is a tremendous resource. But what banks sometimes don’t get is the feedback,” said Craig Timm, senior director of AML at the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS).

“If I file a SAR on a client, it’s likely I won’t hear anything … so it puts the financial institution in a tough spot because they don’t know. Very few instances, as a bank, do you know actual criminal activity is happening,” said Timm.

This defense for banks only goes so far. As subsequent SARs on a customer accrue, the institution must take further action.

“Usually, if you file a SAR, there’s a certain set of criteria where it will be escalated,” said a former AML compliance employee at an FI. Given the sensitivity around any perceived association with Epstein, he spoke to Compliance Week on the condition of anonymity.

“In my experience, the magical number is three [SARs]. Three strikes and you’re out. Then it will usually go up, depending on the size of the organization, to the board of directors or the senior management, saying, ‘Hey, do we exit this person? This is a lot of stuff,’” he said.

While there is no regulatory-defined limit on how many SARs must be filed before exiting a client, an institution will typically look to exit the relationship after the third filing, Rajwani agreed.

“After the third one, it’s very difficult to defend yourself and say, ‘Hey, three times I had reasonable grounds to suspect money laundering, and I permitted it.’ Because at that point, the question becomes: ‘Are you facilitating it?’” he said.

Bank cooperation during investigations

“It’s something that certainly when I was a regulator was always in my head. You need to have a fine that is sufficient to certainly not allow profiting from compliance failures in this kind of situation. I don’t know what the profit here was. The fine should be more than the profit.”

Maria Vullo, former superintendent of the NYDFS, on the Deutsche Bank consent order (2020)

Once an institution is under investigation by a legal or regulatory authority, the wisest course of action is cooperation.

“If you’ve gotten to the point where there’s an investigation, obviously you should cooperate,” Timm said. “… You’re almost too far down the line. There’s some sort of problem there. Even if it doesn’t get to the point of criminal charges being brought, something happened at the institution that got you here that is probably not ideal.”

Still, the choice to cooperate or not is up to bank leaders and their lawyers to decide.

“A lot of institutions do fully cooperate, produce materials very quickly, and voluntarily make their employees available for interviews. … Or they can do it involuntarily,” said Timm, a former Department of Justice attorney. In criminal cases, “The U.S. government can always get a subpoena … whether it’s for witnesses or documents. But there’s cooperation credit in these types of cases, whether it goes to trial or not for saving the government resources,” he said.

Of note, JPMorgan’s and Deutsche Bank’s Epstein-related lawsuits mentioned in this report were civil, not criminal. As such, neither institution admitted wrongdoing in these cases, nor were they obligated to do so by agreeing to settlements. Still, it is worth taking a closer look at their respective levels of cooperation with legal and regulatory authorities during the ongoing years of these cases.

JPMorgan: The institution never cooperated with any civil or criminal suit against Epstein, according to court documents from Jane Doe’s 2022 class-action lawsuit against the bank. Doe’s team of attorneys further asserted that when a subpoena was served on the institution in 2009 by a different Epstein accuser, JPMorgan refused to comply with the subpoena.

Court documents from the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) 2022 lawsuit against JPMorgan alleged the bank did not comply with federal banking regulations regarding Epstein’s accounts until after his death in 2019, six years after terminating his relationship with the bank.

Deutsche Bank: When Deutsche Bank landed in hot water for its dealings with Epstein, it opted for a different approach than stonewalling.

An important distinction must be made: While JPMorgan is U.S.-headquartered, Deutsche Bank AG is a German institution licensed by the NYDFS to operate a foreign bank branch in New York. As such, the NYDFS has broad authority to obtain documents and testimony from any bank it regulates. No subpoenas required.

Nevertheless, the NYDFS, in its 2020 consent order with the bank, commended Deutsche Bank’s “exemplary cooperation” during the department’s yearslong investigation into the bank’s dealings with Epstein, among other, separate AML compliance failures.

“That’s a very important point because the [NYDFS] consent order actually goes to great lengths to discuss the bank’s cooperation and that the bank actually did its own internal investigation and turned it over to the regulator,” said Vullo.

Regulators have statutory authority for how much they can fine an institution, but a bank’s level of cooperation is a significant factor in calculating the amount of a fine, she said.

“I’m sure [NYDFS] could have gone higher than this [$150 million penalty], but it’s always an assessment based upon many factors, including the nature of the offense,” Vullo explained.

“It is really important for regulators, in my opinion, to commend banks for cooperating and for identifying issues and doing internal investigations without regulators requiring it,” she continued. “… Regulators should give credit for that because that’s an incentive for [FIs] to have good compliance cultures.”

Notably, Chip Packard and Paul Morris, the two Deutsche Bank employees arguably most responsible for bringing Epstein into the bank and managing the client relationship for five years, according to a 2022 Jane Doe lawsuit alleging racketeering against the bank, left the institution before the NYDFS fine came down.

“I don’t know how these people left; maybe they were terminated by the bank? Those are all excellent measures for banks to take, which is reflective of a much better culture and also an intention to have a better culture,” Vullo said.

Morris and Packard did not respond to requests for comment on their respective departures from the bank.

Corporate vs. individual accountability

When Morris and Packard of Deutsche Bank conducted their alleged home visit at Epstein’s New York town house in January 2015, they made no record of their so-called due diligence meeting. The broad takeaway was that Epstein “satisfactorily” explained away the allegations of sexual abuse and human trafficking on the table.

The incident is reminiscent of Jes Staley’s “conversation” with Epstein about similar allegations at JPMorgan in 2011, as cited in the USVI lawsuit. In both scenarios, the broad takeaway of an off-the-record conversation—hearsay, essentially—was relayed to senior bank leaders and formalized as an on-the-record justification for retaining Epstein as a client.

Both FIs illustrated corporate governance weaknesses that led to a culture of profit over compliance. A question remains as to whether individual players in these cases should be held responsible for their alleged roles in enabling the Epstein enterprise to flourish while employed by these institutions.

“It’s more important to hold individual employees responsible,” asserted Robert Mazur, one of the world’s leading authorities on money laundering techniques. “Paying fines is a cost of doing business. It’s worthwhile if you have enough evidence to enable you to charge the corporation, but it’s much more important to charge the individuals. The U.S. has a long history, unfortunately, of not going after the individuals.”

Vullo argued that reducing the overall fine imposed on an FI on account of cooperation incentivizes institutions to nurture compliance cultures—but what about the employees who got out ahead of the wreckage? What have they learned from the situation?

Jamie Fiore Higgins, former managing director at Goldman Sachs, believes not holding individuals accountable for misconduct contravenes larger efforts to promote firm-level compliance and actually reinforces a mindset of greed.

“As far as these guys go, was it a coincidence [that they left]? Did they see it coming? At the end of the day, the fact that accountability is at the firm level makes individual players completely free,” said Higgins. “If the institution is writing the check, and these actors aren’t being sought after for retribution, it sends the message you can be a bad actor as long as you jump ship in time. That also reinforces the willingness to push the envelope because at the end of the day, you might get fired or you get another job before that happens.”

Proactive steps forward

The most fundamental way for FIs to build strong AML compliance programs is to start from the top and examine the culture that bank leaders bring to the organization.

What kind of support does the AML department have from the business executives? What level of trust does it have? Living and breathing institutional values of compliance from the top promote the larger buy-in of the business, allowing the AML department to be properly resourced and do its job effectively, Timm said.

A lot of well-run AML programs also proactively engage with law enforcement.

“If, when law enforcement comes to you, you’re assisting them, you’re working together, you’re explaining things, you’re filing good SARs … those are all the things that build credibility so that when, inevitably, something bad moves through your institution, you’re going to get the benefit of the doubt because you built up this long history of showing that you’re acting in good faith,” Timm said.

FinCEN has a public-private partnership forum called “FinCEN Exchange,” which brings institutions together to share information on certain topics, such as trends and typologies in money laundering. It is not a requirement to participate, but many FIs do.

FinCEN also leads a BSA advisory group, which meets regularly and involves working groups that include professionals from the public and private sectors to advise the Treasury Secretary and director of FinCEN on AML.

“Most banks want to do the right thing. They recognize it’s really hard. They see that the government could be very helpful when they share information, so they recognize it’s good for controlling the risk of their institution,” said Timm.

Another proactive step is to enhance internal coordination between know your customer (KYC) and customer due diligence (CDD), said the anonymous former AML compliance employee.

“Traditionally, especially at the larger institutions, KYC and CDD are separate things. The systems don’t talk to each other. There won’t be any sort of interface with your transaction monitoring system,” he said.

More recently, there has been a push toward “perpetual KYC”: continually updating a customer’s KYC file in real time based on new alerts and linking up those updates with the transaction monitoring team.

“Now the encouragement is, ‘Hey, update your files more regularly, as you know them, in real time or within a short amount of time.’ Then when it comes out on the transaction monitoring and investigative end, we can look up that file and say, ‘Hey, this makes sense,’” he said.

However, the wheels of technological progress in this regard move slowly, he said.

“You’re talking about major financial institutions, and they spend a lot of money on this stuff, but they’re still slow. It’s not a perfect science at all. The systems are very old legacy systems, and when you want to do an upgrade, it costs a lot of money to do it,” he said.

As a result, “There is a lot of data that just kind of sits there, and it’s very difficult to keep on top of when you have hundreds of thousands of clients, even high net-worth individuals. It’s hard to keep track of what they’re doing,” he said.

AML technology expert Jeremy Swetenham of KYC360 said an effective AML compliance program is like a three-legged tripod, built on an equal balance of people, processes, and technology. Complex processes, like the ones described by the anonymous AML compliance employee, can be supported by technology through the automation of risk-based processes, which can provide consistency of process and free up high-value skills for better decision-making.

“People are still required when it comes to making decisions. There’s a lot of talk about AI (artificial intelligence) and machine learning, but from a regulatory basis, you can’t point to the black box and say it made the decision,” Swetenham said.

Just in the past five to seven years, the chances of detecting criminal activities have improved significantly, thanks to new approaches; software; and AI techniques such as entity resolution, natural language processing, large language models, and other developments, confirmed Rajwani.

“Financial institutions should take full advantage of these [resources], as human trafficking, child sexual exploitation, labor trafficking, and sextortion are at epidemic levels … and organized crime is taking full advantage,” he said.

Topics

- AML

- Anti-Corruption

- Artificial Intelligence

- Bank Secrecy Act

- Banking

- Case study

- CDD

- Customer Due Diligence

- Deutsche Bank

- Epstein KYC/AML Case Study

- Ethics & Culture

- Europe

- Europe

- Finance

- Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

- Financial Services

- Internal Investigations

- Jeffrey Epstein

- JPMorgan Chase

- Know Your Customer

- KYC

- New York State Department of Financial Services

- NYDFS

- Risk Management

- Surveys & Benchmarking

- Suspicious Activity Reports

- Technology

- United States

Case study: ‘The Banks Behind the Epstein Enterprise’

This Compliance Week case study offers a deep dive into the anti-money laundering compliance failures—and alleged complicity—of JPMorgan Chase and Deutsche Bank, the two banks that enabled the Jeffrey Epstein enterprise to flourish for decades.

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Chapter 4: Investigations into misconduct: What banks can do

No comments yet